Republician American, March 2015

For more information or

to book a performance:

CONTACT STEPHEN COLLINS

978-853-0710 or walt978@aol.com

Or use this form

Or use this form

by Laura Lewis

BRATTLEBORO — When members of the audience enter the Hooker-Dunham Theatre, they do not so much enter an auditorium as step back in time into American poet Walt Whitman’s study in the year 1889. In Charles Butterfield’s effective and evocative set, books are everywhere: piled on Whitman’s desk, on chairs, on tables, on the study rug. Other writings — letters, papers, and scribblings — are scattered on every surface or crumpled on the floor. Early photographs stare impassively down from the walls. A faded pink armchair, the rose background of a Victorian flowered rug, and a red carnation on Whitman’s desk provide splashes of color.

The effect of this set is to make the audience feel as though they are visiting the house museum of a famous writer. However, museums are always tidied up. This room looks as though the writer lived there and was just about to step through the door. And in the play, of course, he does.

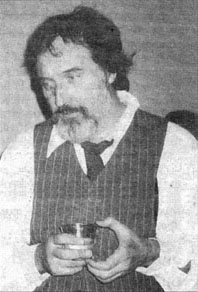

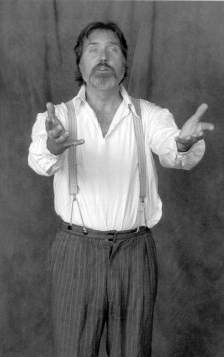

When the elderly Whitman, as played by Boston actor Stephen Collins, steps into his study and with a child-like openness welcomes the audience into his home, they come. In the course of the play, Collins portrays Whitman at several ages and looks very much like photographs of Whitman.

Collins’ Whitman is interested in people, is enthusiastic, optimistic, and loving. Whitman’s writing as presented here glories in mankind and shares his love of the world with the world. In his work, and most of the work quoted in the play is from different revisions of “Leaves of Grass,” he loves things by examining and praising them. He seems to feel that any censoring of his sharings about those he loved was unthinkable because the act of censoring would be unloving and dishonest. In the nineteenth century not everyone understood this philosophy.

Michael Z. Keamy’s play “Unlaunch’d Voices …” introduces Walt Whitman and his work to twentieth century audiences. Keamy has worked on this project for two years, reading everything Whitman wrote, both poetry and prose, as well as many of the biographies and critical works about him. Keamy feels that: “Walt Whitman is considered ‘America’s poet,’ but a large part of the population has either never read him or doesn’t know him.” Keamy has written his one man play to show the relevance of Whitman to our time.

In “Unlaunch’d Voices …” Keamy gives us a Whitman who, in the first act, is young and self-centered, concentrating his life on his writing, his living, his loving. The second act takes Whitman to Washington in 1862 to look for his brother who has been wounded in the Civil War. His brother recovers, but Whitman cannot leave the other wounded without trying to help them. He spends the next two years working in Washington, writing reports for the government and for New York papers. Every day Whitman visits the hospitals and works with the wounded until his own health gives out, and he returns to New York to recuperate. In this act, Keamy says, “Whitman learns to be selfless.”

Stephen Collins of Concord will be performing his one-man show, “An Evening With Walt Whitman,” next weekend at the Hancock Church In Lexington.

The text of the play is divided between direct quotes from Whitman’s writings and from the notes taken by Horace Traubel while the elderly Whitman reminisced about his life and writing. To Keamy’s credit the final product has much more of the feel of a story than that of a term paper. Audiences come to know this person rather than to be told about him.

As he worked on the play, Keamy the playwright was surprised that Whitman was so full of contradictions. “He assumed roles. There was his public image, and his private image which was kept private. We will never know everything about him. The playwright’s challenge is to constantly ask himself: ‘Am I being true to the man?”‘ Actor Stephen Collins was surprised at the poet’s boundless optimism and his range. “He was so well-read, the Bible, Eastern mysticism; he used to walk up and down the beach declaiming Homer. He was interested in so much.”

The written work, however, is only the first step in the dramatic process. Directing, acting, and all of the technical aspects must come together successfully to create a satisfactory whole and here they do. Thanks to Keamy’s sympathetic direction and Collins’ strongly created and engaging persona, the audience comes away from the one and one-half hour play interested in and affectionately disposed to Walt Whitman. Anyone interested in knowing more about this great figure from America’s past should enjoy an evening with “Unlaunch’d Voices …”

“Unlaunch’d Voices …” will be presented at the Hooker-Dunham Theatre and Gallery, Oct. 8, 9, and 10. Friday and Saturday performances at 8 p.m., the Sunday matinee at 3 p.m. General admission is $9, $8 for seniors and students. Call (802) 254-9276 to reserve seats. Hooker-Dunham is located at the end of the alley and downstairs at 139 Main Street, Brattleboro, Vermont

Laura Lewis is a freelance writer for the Reformer.

by Ruth Iyengar

On Thursday, Jan. 29, Walt Whitman came limping into Schein Hall from a side aisle with his cane and greeted the audience with “How’d you do? “How’d you do?” From that moment on, you felt an immediate rapport with the man who heard America singing.

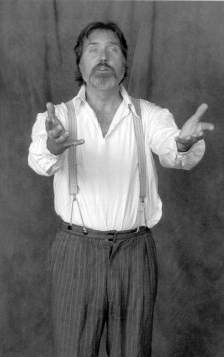

Collins as older Whitman

Stephen Collins brilliantly portrayed Whitman in Unlaunch’d Voices, a one-man play, conceived by him, written and directed by Michael Keamy and, heretofore, performed across New England. During the evening Whitman was transformed from a man of 70 to a young man of 37, then back again to a 70-year-old.

We felt Whitman’s ecstasy as he lay on the beach next to his lover. “When I heard at the close of day…And his arm lay lightly around my breast – and that night I was happy.” Yet later, how well we knew his pain as he fell on his knees in utter torment, head in hands, realizing full well the lifelong struggle he would endure with his sexuality. (The word homosexual did not even enter the lexicon until the 1880s.)

During the Civil War Whitman was moved to spend time – four years in all – in hospitals and camps tenderly caring for the wounded and dying soldiers, most of them in their mid-teens. As Whitman knelt by the dying Civil War soldier on the battlefield, you sensed his loss. When writing to the boy’s parents he described how their son looked – his vibrant eyes, his flowing hair – words of comfort to a grieving family. The actor’s eyes were filled with tears when, as Whitman, he walked through the makeshift hospitals, stopping to grasp a hand, caress a forehead, cover a dead body with a blanket, tucking it over and around the boy’s head and feet. The deep emotions he felt resonated with the audience as they related to today’s world – more war, more loss, more grief.

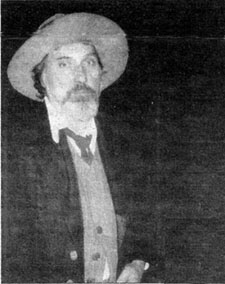

With salt and pepper beard and 6-foot-5-inch height, Stephen Collins resembles Whitman. His commanding voice modulates effectively – frail when portraying the 70-year-old, robust and vibrant at 37. The gray felt hat Collins wore was Whitman’s signature piece. A black frock coat was worn over a vest, white shirt with red tie, and trousers. When Whitman was transformed to a much younger man, the frock coat, vest and tie were quickly tossed aside. We see the familiar Whitman swagger as he strolled down a Boston street thinking “Look at me, America. I am Walt Whitman!”.

The set for Unlaunch’d Voices was cleverly arranged by Linda Kramer with 19th Century antiques – a desk, rattan chair with cushions, a book stand, numerous books strewn everywhere, and oriental rugs. Collins’ movements down the center aisle during the performance – connecting with the audience, asking a question, looking directly at someone – lent an intimacy to the evening.

Collins as young Whitman

Whitman ruminates on the failure of Leaves of Grass in the U.S. and reads a letter of praise from Ralph Waldo Emerson (which he printed in the second edition of Leaves without Emerson’s approval)… but then speaks of arguing with Emerson, defending the integrity of Leaves against Emerson’s suggested edits. In his later years, Whitman was supported by a group of English writers who believed in his work.

If the measure of a life lies in the acceptance by one’s peers, Whitman himself probably would have conceded that his life was a failure. If the measure lies in being true to oneself, then Whitman’s stubborn insistence on writing only the truth, in his own voice, in Leaves of Grass created an American legacy that will never fade far from view.

Ruth Iyengar has been a member of the Sanibel community for some years and is presently serving on the BIG Arts On Stage committee.

– Karen Nelson contributed to this review as well

by George W Hayden

A serenely acted one-man show “Unlaunch’d Voices” starring Shakespearean actor Stephen Collins hosted by the indefatigable producer Wendy Bidstrup proved a meticulously mounted showcase. The Marion Art Center, like a miniature Ford Theatre (Washington, D.C.) with its 19th-century portraits and one balcony box seat was a most appropriate ambiance for Collins’ noteworthy revitalization of one of our nation’s greatest war-time genre poets.

The effect of this set is to make the audience feel as though they are visiting the house museum of a famous writer. However, museums are always tidied up. This room looks as though the writer lived there and was just about to step through the door. And in the play, of course, he does.

In his lively introduction as Whitman to his audience, I believe Collins singled out this reviewer as an “old elephant.” His tone set a captivating and educationally refreshing familiarization with this great creator of free verse: “Leaves of Grass” (self-published, 1855).

As a journalist, Whitman wrote for the long-defunct Brooklyn Eagle and Long Island Democrat Collins presents an intimate study, yet shies away from the symphonic and flamboyant side and nature of Whitman. His Concord letter from Ralph Waldo Emerson is an effective dramatic device which allows him to show how these visionary precursors of spiritualism and transcendentalism kept through correspondence an unified contact with each other long before the computer. He successfully refutes with Whitman’s own writings those critics who blackballed this apostle as obscene, and in the one hour plus presentation given at M.A.C. there was some deletion from the homo-erotic specifically in the battlefield poems and letters Whitman wrote while serving as a male nurse during the Civil War.

This is a most healthy, soulful celebration of the human body, wherein “sex advances the horizons of discovery.” Whitman said “censorship is always bad, always ignorant,” and that “animals were not demented with the mania of owning things.”

Americans ignored Whitman’s work, while Europeans embraced him. He lived in poverty all his life and was judged to have been unsavory by his detractors. About war, he wrote, “I’m at peace with God and death.”

Collins’ performance can be booked for schools and colleges, etc. It’s a literate and refreshing approach. He has played in the poet’s hometown area, Huntington, Long Island, and will be at Brattleboro, Vermont in October. His Whitman will tantalize and reveal much.

Recent Comments